By Chrislyn Laurie Laurore

Photographs provided by Divers With A Purpose

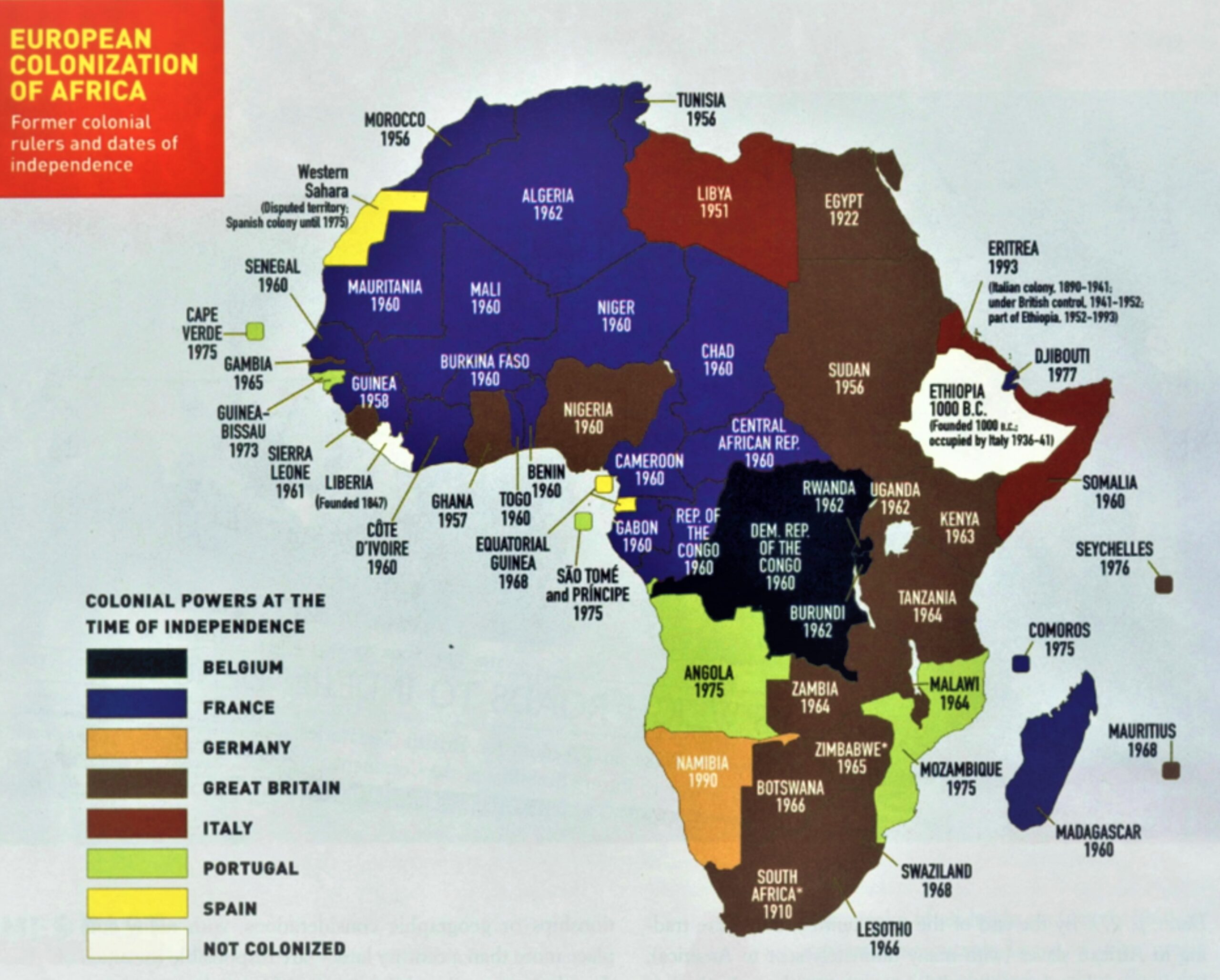

According to the captain’s account of the shipwreck, the L’Aurore, a French vessel, left present-day Mauritius for Mozambique in November 1789 to pick up enslaved people en route to its final destination, the French Caribbean.

In January 1790, as enslaved people were boarding the ship in the harbor of Ilha de Mozambique, the 356 already on board attempted to mutiny, during which four of them drowned. Because of the insurrection, the crew locked the enslaved men below deck. Women and children were kept in the main cabin. On February 17, 1790, when about to take off, the L’Aurore was hit by a typhoon while at anchor with a cargo of 600 enslaved Africans. The crew refused to unlock the lower deck and abandoned the ship and the Africans to their fate. By morning, 331 of them had perished. The ship was partially salvaged immediately after sinking but then lay undisturbed for 230 years.

On a tranquil evening at Legacy Beach in Monrovia, Liberia, I sat down with Kamau Sadiki—a man whose life work delves deep beneath the ocean’s surface, uncovering the silent yet profound stories of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. A retired engineer, Kamau’s journey has taken him from the academic halls of Howard University in Washington, D.C., to the depths of the Atlantic, where he now serves as a lead instructor in the underwater archaeology program for Diving With a Purpose (DWP).

As Kamau recounted his involvement with DWP, it was clear this was more than a professional endeavor; it was a calling. Founded in the early 2000s by Ken Stewart, a visionary community organizer, and Brenda Lazendorf, an archaeologist at Biscayne National Park, DWP emerged from a serendipitous collaboration. Their mission? To document shipwrecks in Biscayne’s waters—a task that Brenda lacked resources to undertake. Ken, inspired by the untapped potential of skilled Black scuba divers, mobilized a small cohort to train in underwater archaeology, sparking a movement that now spans decades and has trained over 500 divers worldwide.

Their work has evolved to uncover and memorialize shipwrecks from the transatlantic slave trade—vessels Kamau poignantly refers to as “vessels of enslavement.” Of the 12,000 ships involved in the slave trade, an estimated 40,000 voyages were made across the Atlantic, yet fewer than 15 of these wrecks have been scientifically documented. Kamau has personally worked on six of these haunting sites, bringing to light the stories of those who endured unimaginable suffering aboard them.

The process is both painstaking and deeply respectful. Divers meticulously map and document the wrecks, creating composite images of the sites while treating them as sacred spaces. For Kamau, the experience transcends the scientific. “The ocean has memory,” he reflects, describing how the ancestors lost on these voyages communicate through the depths. “They’re not going to speak to us in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. They speak to us through our hearts, through our spirits.”

Kamau shared his belief that every dive is a spiritual journey—a chance to listen, connect, and honor the lives lost. With over 1,600 dives under his belt, nearly a third of which have been on these “vessels of enslavement,” he approaches each mission with reverence. Before entering the water, divers hold ceremonies to acknowledge the history and humanity of those who perished. “We know these are sacred sites. There’s been a loss of life, and we must treat them with the dignity they deserve,” he said, visibly moved.

As Kamau eloquently stated, “The challenge is learning how to listen.” And perhaps, as we learn to hear the whispers of history carried by the waves, we might better understand our present and chart a more conscious path forward. These sites, sacred and haunting, serve as final resting places for countless souls who perished during one of history’s darkest chapters.

A Chilling Experience

One of Kamau’s most poignant experiences occurred in 2013 off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa, on the wreck of the São José Paquete. A Portuguese vessel, the ship sank in 1794, carrying 212 enslaved Africans, all of whom perished in the icy waters. During an initial survey dive, Kamau encountered a fragment of the ship’s material lodged in the underwater rock. As he reached out to touch it, he was overcome by a flood of emotion—an inexplicable, visceral response to the collective pain and horror of those who had perished. “I heard their screams in my body and in my head,” he recalls. “I was brought to tears underwater.”

This encounter cemented his commitment to amplifying the voices of the ancestors lost to the sea. Kamau’s work, along with his colleagues, goes beyond archaeology; it is a reclamation of history and a call to honor the dignity of lives erased by centuries of oppression. Shipwrecks, often forgotten or romanticized, become sites of reverence and reflection under the stewardship of DWP. These dives remind us of the enormity of the transatlantic slave trade.

From the Guerrero to the Clotilda

The Guerrero and the Clotilda, two infamous vessels tied to the transatlantic slave trade, represent not only submerged fragments of history but also the enduring resilience of the African diaspora. Through the work of the DWP initiative, these stories are being brought to the surface, creating a bridge between the past and the present.

Off the coast of Key Largo, Florida, lies the Guerrero, a pirate slave ship wrecked on Christmas Day, 1827. This vessel, carrying over 500 enslaved Africans, met its fate after a desperate chase by the British African Squadron’s HMS Nimble. Tragically, while 41 lives were lost in the wreck, many others fell victim to subsequent enslavement schemes. The journey of the remaining captives is equally heart-wrenching. Following years of turmoil in Key West, Florida, and subsequent enslavement in St. Augustine, a fraction of the survivors—92 individuals—found their way to Liberia, established by American Colonization Society (ACS) in 1822 on the West Coast of Africa as a colony for freed and recaptured African-American slaves from the United States. These 92 individuals settled and established a settlement called New Georgia in Liberia. Their descendants provide living testimony to this incredible story. “Meeting these descendants has been the most profound part of our work,” Kamau shares. “The power of these connections, the emotion of tracing their ancestors’ journey, is beyond words.”

DWP’s work is not just about unearthing shipwrecks but also empowering communities to take ownership of their stories. In Liberia’s New Georgia, DWP wants to inspire the next generation by teaching local youth to swim, dive, and ultimately engage in maritime archaeology. The long-term vision? To have these young Liberians dive on the Guerrero’s wreck site in Florida, completing a full-circle journey to their ancestral origins.

The Clotilda, the last known slave ship to transport Africans to the United States, holds a unique place in history. Unlike the Guerrero, the Clotilda’s wreck has remained remarkably intact, offering unparalleled insight into the horrors of the Middle Passage. “Of the 12,000 slave ships that crossed the Atlantic, this is the only one we can clearly see as a ship,” Kamau emphasizes.

The significance of preserving the Clotilda extends beyond its physical structure. It represents a tangible connection to the descendants of the enslaved people who endured its journey. In Africatown, Alabama, the community of Clotilda descendants continues to honor their ancestors’ legacy, creating a powerful heritage trail that intertwines their stories with the shipwreck’s historical footprint.

For travelers, these stories invite a deeper exploration of Africa and its diaspora. From beneath the ocean at Camp Bay to the vibrant streets of New Georgia, Liberia, every corner of the continent holds layers of history waiting to be discovered.

Kamau Sadiki on Travel, Diving, and Mozambique’s Hidden Gems

Chrislyn: Kamau, this being a travel and lifestyle magazine, could you tell us about your favorite places to visit or dive?

Kamau: That’s a tough one because all the places I’ve dived hold a special place in my heart. But if I had to choose, Ilha de Mozambique stands out. It’s an idyllic island off the coast of Mozambique with a population of about 14,000 people. It’s a former Portuguese colonial hub with stunning architecture and a unique cultural charm. I’ve been visiting since 2013—probably 15 or more times now—and it never ceases to amaze me.

Chrislyn: What makes the journey to Ilha de Mozambique so memorable?

Kamau: Getting there is part of the adventure. First, there’s a 20-hour flight to Johannesburg, followed by an overnight stay. Then, you take a three-hour flight to Nampula and embark on a four-hour drive to the coast. The drive is fascinating—you pass through little towns and villages that give you a glimpse of local life. When you finally arrive, the island greets you with its beauty and vibrant culture.

Chrislyn: What role does Diving with a Purpose (DWP) play on the island?

Kamau: We’ve partnered with the local community to develop eco-tourism and cultural heritage initiatives. We train Mozambicans in diving and underwater archaeology so they can reclaim their stories and share their history. One young woman we trained is now guiding eco-tours and teaching about the island’s mangroves and environmental stewardship.

Chrislyn: That’s inspiring! What’s the food like on Ilha de Mozambique?

Kamau: The food is amazing. I’m vegan, so I always enjoy their greens, especially with rice. They make this delicious spinach-like dish, and I’m a fan of their peri peri hot sauce. The locals know to prepare something special when they see me coming!